Sometimes courtroom dynamics reflect or even exacerbate the dynamics in a relationship. Sometimes courtroom dynamics are are played out on a macro scale.

Take, for example, the recent Womens’ Aid “campaign report” : Nineteen Child Homicides, which deals with tragic cases where fathers have killed their own children in the context of post-separation contact arrangements (and sometimes themselves or the childrens’ mother), and which is critical of what they say is a culture in Family Courts of prioritising a fathers right to contact over a child’s need for safety (of which, more in another post).

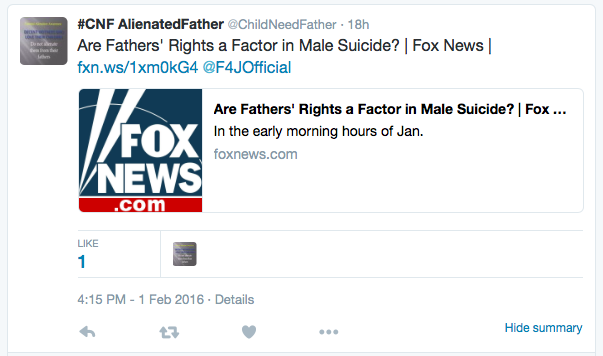

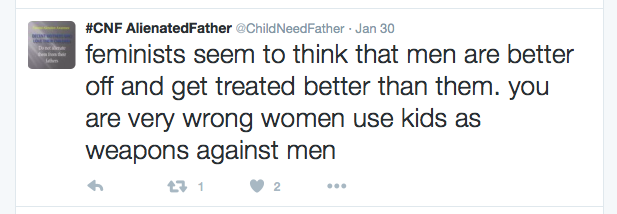

And, in the other corner, take Fathers’ rights campaigners, an example of which you see here, who express the same issue rather differently – denial of contact as a causal factor for male suicide (often accompanied by child homicide, as in the linked Fox News Article). They are also critical of the culture in the Family Courts, which they say prioritises mothers over fathers, and treats fathers with suspicion.

How to reconcile these two polarised views of the world? Because they surely can’t both be right all the time?

What is sad is that there is a degree of validity in both perspectives, but as with the individual disputes there is a tendency on both sides to blame the system, and an inability to talk to one another constructively and an attempt to grab the attention of the audience by making impactful statements and shocking statements. Characteristic of both campaigns is a tendency to imply or directly assert bad faith by those working in the system, which is generally an unhelpful starting point (although it may be a feature in some cases, we need to be open to looking for other explanations for failure too).

Whatever the failings of the system (and they are many), one simply cannot blame anyone for the murder of their own children but the parent who has carried out the act, although one may look for ways to better understanding why that person carried out such a desperate act, and how we might better avoid such scenarios. Personally, I think the answers are more complicated than “no contact for all fathers with a history of violence” or “let fathers have contact or this is what happens”, which are ultimately pretty much the arguments I have heard made on many, many occasions by one or other “party” to this dispute about how to deal with contact (I’ll let you work out which party makes which proposition).

No doubt this irksome failure to take sides makes me simultaneously a Feminazi and an idiot with no understanding of risk or domestic abuse. I take heart in the knowledge that both camps will at least agree I am a callous fool who does not care about children.

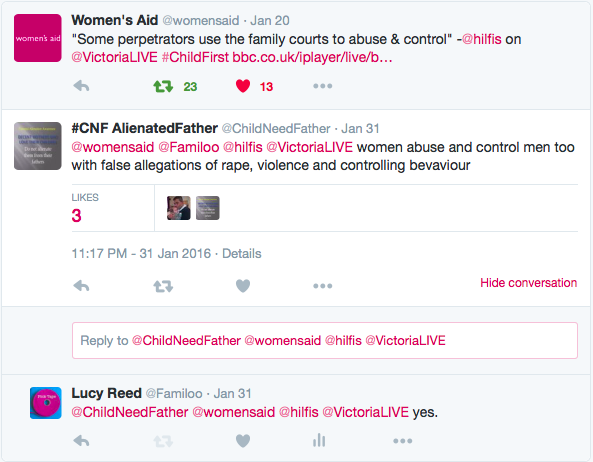

I wish we could have a proper conversation about these things without it feeling like walking on eggshells, without people feeling compelled to respond with a counter argument. See this tweet, and short exchange with @childneedfather on twitter as an illustration – it is simply not possible to agree with any aspect of one “side’s” argument without the other “side” pointing out how their argument is better. It is seemingly impossible for either side to concede the other has a bit of a point : “if you’re not for us you’re against us”. (Incidentally, I am not picking on @childneedfather, with whom I have had some sensible discussions – it is just a recent illustration for me of a wider issue, a sort of ingrained knee jerk reaction).

I will probably be criticised for this blog post because we can’t talk about this stuff like grown ups. Hey ho. I’m used to being in the line of fire for pointing out the uncomfortable and for refusing to stay one side of the line.

Incidentally, I am writing a longer blog post about the Nineteen Child Homicides Report. It is unlikely to agree with everything the report says. Neither will it poo poo it and dismiss it out of hand.

Post script, whilst just clearing out my desktop I came across this tweet exchange which I screen-shotted to remind me to write a post along these lines some weeks ago. I had forgotten these when I wrote the post.

I too wish there could be a “grown-up” discussion and debate about these issues.

The problem is that both these separate lobbies see life through a gendered lens, and certain issues are perceived as women-only or men-only issues, and that perception is encouraged by the single-gender organisations. There are very few issues in family breakdown that are gender-specific; the only two I can think of are paternity fraud and parental responsibility for unmarried fathers. Everything else – be it false allegations, domestic abuse, parental alienation, homelessness, debt, being unable to access funds, depression and other mental health issues, the threat of the former spouse/partner absconding with the children, to name just a few – are all experienced by both men and women. Those issues don’t respect gender, social status or age, and no-one should pretend that these issues only affect one gender.

When mothers and fathers are divided into these two separate gender camps, they can end up with a rather warped view of their own situation; there is little to no balance offered, no differing perspective, no real understanding of why their former spouse or partner may be acting in a particular way. Often it is it hearing differing or opposing perspectives and thoughts that can make a real difference to how an individual understands and deals with their own situation. Being part of a balanced and gender-neutral environment aids the understanding, and offers a holistic approach to emotional healing and recovery.

Thanks Ruth, I agree that these issues affect both men and women and that the very polarised gendered perspective can be unhelpful. But I do think that gender plays a role and there are patterns of power and behaviour which tend to play out along gender lines (I’m not allowed to say that either) and which affect people differently as a result of their gender. But balance is the key, isn’t it?

This publication by Women’s Aid is a re-vamp of their attempt to do the same thing back in 2006 with twenty-nine child homicides, which was responded to by LJ Wall: https://www.judiciary.gov.uk/publications/twenty-nine-child-homicides-report/

It wasn’t justified then, it isn’t justified now. In the same 10 year period the Women’s Aid report covered there were several hundred homicides of children by their mothers. Sadly mothers and fathers kill their children in almost equal measure and it’s usually the new partner of a mother who is the greatest risk to children, not the father.

Before pointing the finger at others, Women’s Aid might want to get their own house in order, this tragic story occurred in a Women’s Aid refuge: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-34845765

The serious case review for the P Children case held up by Women’s Aid as an example of the problem can be found here: https://www.safeguardingchildrenbarnsley.com/professionals-and-partners/serious-case-reviews.aspx

It makes depressing reading and all too familiar to those involved with the family courts.

Thanks Brian, those are some of the issues I’m currently writing a post about. Where do you get your “several hundred homicides” by mothers from? Is there a statistic or is it just based on observations of news reports?

3 Children a Week are killed by their Mothers (primarily) in England – 210 children every 16 months.

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/three-children-a-week-ndash-the-death-toll-from-abuse-1061272.html

Mothers kill children far more than any other group, Table 4–4 Child Fatalities Page 61 of link

http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/cm2013.pdf

Great post Lucy. It seems to me that whilst there are no doubt issues in the minority of cases which both sides of the gender (for want of a better description) want to address, their manner of addressing it is to cite the extreme cases and outcomes which simply polarise the opposing camp further.

If only both “sides” would recognise (and empathise) with the other, and sit down together and have a constructive discussion about the system, the perceptions or reality, perhaps we could see some concrete changes that would actually help the parents and children who are stuck in these divorce and separation battlefields.

DEar Lucy,

Thanks for your post. Neither of the opposing sides in this ‘debate’ acknowledge the balance that has to be struck by the courts in determining applications for (old-speak) contact. Arguably it is about balancing risk of one sort of harm (the remote risk of the dreadful events on which the 19 Child Homicides report focuses) against that of another sort of harm (depriving the child of a meaningful relationship with the father (as it usually is)) – perhaps analogous to the risk balancing exercise inherent in a bail decision by the criminal courts. The report quotes Wall LJ along the lines that ‘a parent with a history of DV cannot hold themselves out as a good parent’. If that were approved case-law (I have heard a reference to it being the position in New Zealand but have no source for this) it might make the court’s task simpler; but arguably the costs would then fall in a different place. It is probably right (but also way too simplistic) that a child’s safety must come ahead of contact, but can the courts assume that the risk of such a rare event (and it must be rare given how much contact the courts do order) is so great that direct contact cannot be allowed where there is a history, perhaps denied, of DV?

Well the answer to your last question is that if there is a history of denied DV the court may need to decide whether or not the denial is correct or if in fact the DV took place – before it can properly assess that risk.

I don’t think it is controversial that a history of DV IS A failure in parenting, but of course that does not necessarily mean a parent has not reformed or has nothing to offer. And in itself it does not tell us the level of risk.

3 Children a Week are killed by their Mothers (primarily) in England – 210 children every 16 months.

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/three-children-a-week-ndash-the-death-toll-from-abuse-1061272.html

Mothers kill children far more than any other group, Table 4–4 Child Fatalities Page 61 of link

http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/cm2013.pdf

Children’s deaths are a tragedy, whether the perpetrator is the mother or father or another.

All of these children’s deaths should be treated as equally important by the authorities and campaign groups, not just based on the gender of the perpetrator.

To protect children, it is necessary that preconceived ideas and biases about perpetrators do not get in the way of good social work and family court practice.

ah for adult conversations between folks capable of being reasonable. Nicely put Lucy – I look forward to your post on the women’s aid article.