Sometimes courtroom dynamics reflect or even exacerbate the dynamics in a relationship. Sometimes courtroom dynamics are are played out on a macro scale.

Take, for example, the recent Womens’ Aid “campaign report” : Nineteen Child Homicides, which deals with tragic cases where fathers have killed their own children in the context of post-separation contact arrangements (and sometimes themselves or the childrens’ mother), and which is critical of what they say is a culture in Family Courts of prioritising a fathers right to contact over a child’s need for safety (of which, more in another post).

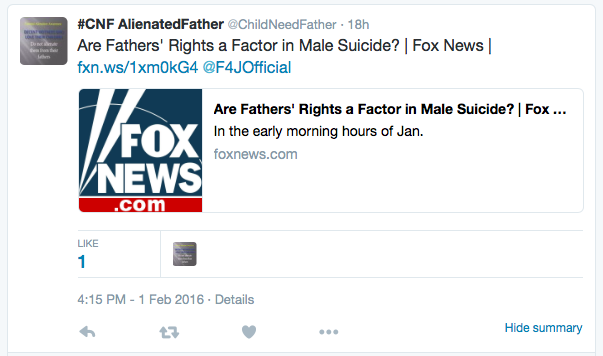

And, in the other corner, take Fathers’ rights campaigners, an example of which you see here, who express the same issue rather differently – denial of contact as a causal factor for male suicide (often accompanied by child homicide, as in the linked Fox News Article). They are also critical of the culture in the Family Courts, which they say prioritises mothers over fathers, and treats fathers with suspicion.

How to reconcile these two polarised views of the world? Because they surely can’t both be right all the time?

What is sad is that there is a degree of validity in both perspectives, but as with the individual disputes there is a tendency on both sides to blame the system, and an inability to talk to one another constructively and an attempt to grab the attention of the audience by making impactful statements and shocking statements. Characteristic of both campaigns is a tendency to imply or directly assert bad faith by those working in the system, which is generally an unhelpful starting point (although it may be a feature in some cases, we need to be open to looking for other explanations for failure too).

Whatever the failings of the system (and they are many), one simply cannot blame anyone for the murder of their own children but the parent who has carried out the act, although one may look for ways to better understanding why that person carried out such a desperate act, and how we might better avoid such scenarios. Personally, I think the answers are more complicated than “no contact for all fathers with a history of violence” or “let fathers have contact or this is what happens”, which are ultimately pretty much the arguments I have heard made on many, many occasions by one or other “party” to this dispute about how to deal with contact (I’ll let you work out which party makes which proposition).

No doubt this irksome failure to take sides makes me simultaneously a Feminazi and an idiot with no understanding of risk or domestic abuse. I take heart in the knowledge that both camps will at least agree I am a callous fool who does not care about children.

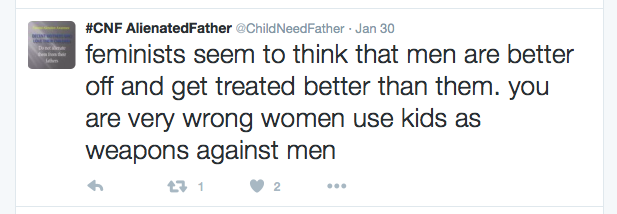

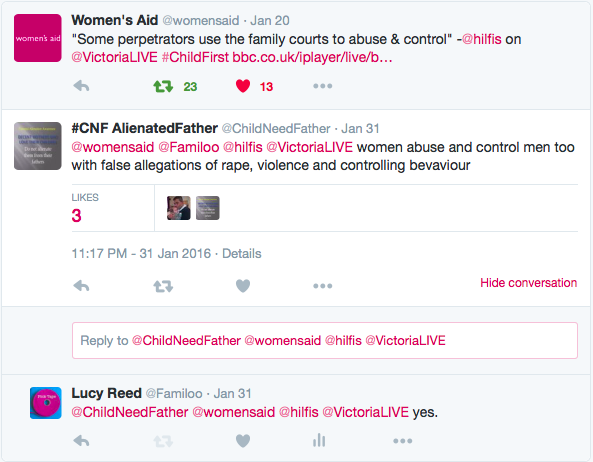

I wish we could have a proper conversation about these things without it feeling like walking on eggshells, without people feeling compelled to respond with a counter argument. See this tweet, and short exchange with @childneedfather on twitter as an illustration – it is simply not possible to agree with any aspect of one “side’s” argument without the other “side” pointing out how their argument is better. It is seemingly impossible for either side to concede the other has a bit of a point : “if you’re not for us you’re against us”. (Incidentally, I am not picking on @childneedfather, with whom I have had some sensible discussions – it is just a recent illustration for me of a wider issue, a sort of ingrained knee jerk reaction).

I will probably be criticised for this blog post because we can’t talk about this stuff like grown ups. Hey ho. I’m used to being in the line of fire for pointing out the uncomfortable and for refusing to stay one side of the line.

Incidentally, I am writing a longer blog post about the Nineteen Child Homicides Report. It is unlikely to agree with everything the report says. Neither will it poo poo it and dismiss it out of hand.

Post script, whilst just clearing out my desktop I came across this tweet exchange which I screen-shotted to remind me to write a post along these lines some weeks ago. I had forgotten these when I wrote the post.